Thailand Had Notoriously Harsh Drug Laws. Now Weed Is Legal—and That's Making Things Complicated

Bangkok’s Khao San Road has been the heady gateway to Southeast Asia for generations of backpackers. Flip-flopped arrivals are met with a sensory cacophony: blistering sunshine, the pungent waft of red chili hitting smoldering works, and, for the more reckless, a smorgasbord of mind-tweaking drink and drugs procured down back allies and dimly lit bars. Saccharine marijuana smoke was never far away, nor was tales of hapless foreigners hauled off to the city’s infamously fetid jail, dubbed the “Bangkok Hilton,” for smoking a mere joint.

But times are changing on the Khao San Road. On June 9, Thailand became the first country in Asia—and only the third in the world, after Canada and Uruguay—to decriminalize cannabis nationwide. (In the U.S., cannabis is federally prohibited but can be consumed recreationally in 19 states and the District of Columbia.) Today, tourists strolling the Thai capital have their pick of dozens of shops and stalls emblazoned with neon marijuana leaves selling glistening buds of white widow, Hindu kush, and lemon skunk.

Every morning, hawkers stack bricks of weed and hashish on foldable metal tables. Glass jars akin to a 1930s candy shop overflow with gummies laced with tetrahydrocannabinol, or THC, the chemical that gives cannabis its trademark “high.” Even 7-Eleven sells cannabis-infused drinks and beauty products, while restaurants offer soups, curries, and pizzas spiked with ganja leaves. Ready-rolled joints cost 100 baht ($2.80), or two for 180 baht ($5). Meanwhile, police stand idly by or even line up to pick up a baggie of their own.

“It’s amazing, I didn’t know weed was legal until I got here,” says Magnus Pedersen, 22, from Norway, who is used to visiting Amsterdam’s famous coffee shops. “Being able to blaze up on a Thai beach is another level.”

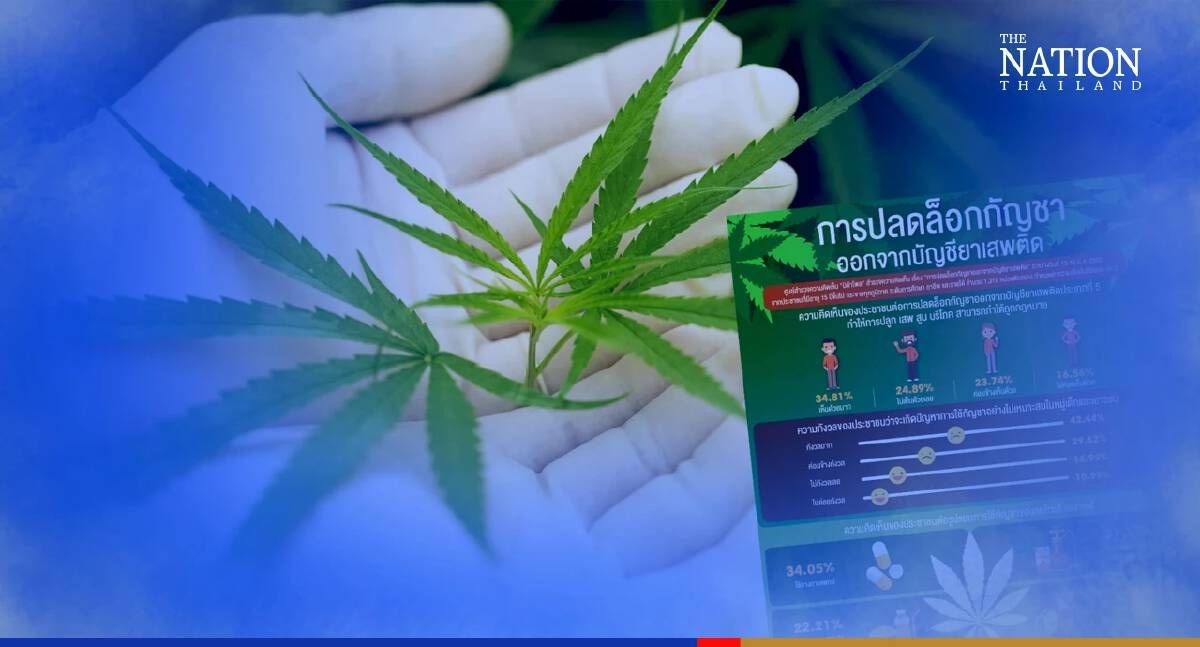

It’s a stunning U-turn for a country known for some of the world’s harshest drug laws. Thailand has the largest prison population among the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—some 285,000 people—and more than 80% of inmates are incarcerated on drug-related charges. Ironically, that draconian legacy inadvertently lies behind the sweeping decriminalization. Last December, Thailand unveiled progressive new narcotics legislation after consultation with international bodies like the U.N. in a bid to lower the prison population by getting addicts out of cells and into treatment. However, the interministerial body that oversees drug policy couldn’t decide on the specific limits to be placed on cannabis. This was chiefly because a flagship policy of Health Minister and Deputy Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul’s Bhumjaithai Party—a key ruling coalition partner—was to decriminalize the plant.

On June 9, the six-month deadline for agreeing on cannabis regulations expired essentially because Anutin kept stalling and, according to sources, threatened to bring down the government if committee members went around him. In that vacuum, cannabis became legal by default. “Today, society is for the most part knowledgeable, understanding, and ready to consume cannabis the right way,” Anutin said Aug. 10. “More people will understand it over time.”

Anutin’s pitch was that cannabis could become a valuable cash crop to help alleviate poverty among rural farmers. In truth, it was simply the most popular of several policy gimmicks his upstart party flirted with before Thailand’s 2019 general election. Since decriminalization, Anutin has given away 1 million cannabis plants to households in well-rehearsed publicity stunts. (Critics also point out that Anutin’s brother is on the board of a company that produces hemp, although Anutin denies any impropriety.)

Anutin maintains that Thailand’s low costs and strong agricultural infrastructure—it’s already among the world’s top exporters of rice, seafood, and sugar—make it well placed to become a cannabis powerhouse, cashing in on a growing trend toward medical and recreational decriminalization around the world. Global sales for medical cannabis were estimated at $37.4 billion in 2021, according to market-intelligence firm Prohibition Partners’ Global Cannabis Report, which predicts the market will soar to more than $120 billion by 2026. Thailand’s cannabis market is estimated to reach $1.2 billion by 2025.

Looking to benefit are some 4,200 inmates in prison for cannabis-related offenses who became eligible for release the same day decriminalization came into force. Those convicted of illegal cultivation even had their seized equipment—ultraviolet lights, grow tunnels, irrigation apparatus—returned to them. Many went from behind bars to back in a resurgent, legal business within hours.

Still, Thailand’s frenzied weed free-for-all has met growing pushback from some in the medical establishment as well as social conservatives. On June 17, Thailand absorbed cannabis into an existing law governing traditional medicine, meaning its sale was banned to under-20s, pregnant women, and breastfeeding mothers. Growing cannabis plants for personal consumption is allowed, but selling plants or derivative products officially requires a license. Whereas cannabis flowers can have unlimited quantities of THC, derivatives like gummies can have only a token of 0.2%. Smoking cannabis at home may be legal, but lighting up in the street is discouraged by existing laws governing behavior deemed a “public nuisance” and could mean a $700 fine or three months imprisonment.

It’s an extremely confusing picture where different government ministries consistently say contradictory things. Despite the lack of regulation and rampant proliferation, Anutin continues to deny that recreational cannabis is legal, but says that it can only be used for “medical purposes.” He also said that “we won’t welcome” marijuana tourists even as the Thai Food and Drug Administration (FDA) mulls setting up a “cannabis sandbox” that allows tourists to light up freely in designated zones. Plus there are the challenges of Thailand’s becoming a cannabis exporter given logistical barriers to shipping what’s commonly deemed a controlled narcotic, not to mention competition from mature markets elsewhere. Meanwhile, the real possibility that the law can lurch back to draconian prohibition hangs heavy over the budding industry.

“One way or another, policy clarity is needed,” says Jeremy Douglas, regional representative for Southeast Asia and the Pacific at the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime. “It would be a shame if Thais or foreign tourists got caught on the wrong side of the law because of mixed messages or perceptions.”

Few appreciate the stakes better than Chokwan “Kitty” Chopaka, a longtime cannabis legalization advocate who opened a hole-in-the-wall weed dispensary by Bangkok’s bustling Asok intersection just two days after decriminalization. Her tiny premises is an Aladdin’s cave of cannabis delights, selling flowers, gummies, and huge bamboo pipes. In her first week, she cleared more than $28,0000, despite being open only from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. “People were complaining that they couldn’t buy weed outside of office hours,” she says, “but I still had so many people queuing outside that I had to hire a security guard.”

Then, on July 27, a Thai official issued a directive to “arrest and prosecute” those selling cannabis without “permission,” saying dispensaries like Chokwan’s “should never have existed.” The order sent panic across the nascent cannabis industry. Chowan decided to shut her shop and rushed to the FDA to figure out how to get a license. When she arrived, the offices were thronged by dispensary owners. She eventually left with a receipt acknowledging her application for a license. Hours later, a top health official announced that the arrest order had been rescinded since the license that dispensary owners were ordered to obtain didn’t exist yet. Chowan reopened the next day.

“We’re in limbo right now regarding the rules,” Chokwan says. “I can’t plan the next three months; I can’t even plan the next week. It’s crazy.”

Her angst is understandable given the extremely punitive measures that Southeast Asian governments have used to rein in narcotics for four decades.

Cannabis was traditionally popular across Indochina in cooking or as a medicinal herb to treat myriad ailments, including headaches, cholera, dysentery, malaria, asthma, digestion, parasites, and postpartum pain. But after Washington stationed tens of thousands of American troops at military bases in Thailand during the 1960s, the local marijuana industry exploded with cheap, potent pot, especially the infamous “Thai stick.” In 1967, one dumbfounded DEA agent dubbed Thai weed “the Cuban cigar of the marijuana world,” writes Peter H. Maguire in Thai Stick: Surfers, Scammers, and the Untold Story of the Marijuana Trade.

During the 1980s, the U.S. government put diplomatic pressure on Bangkok to partner with them in stamping out the cannabis trade. In 1988, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 463,000 lb. of Southeast Asian marijuana heading for American pipes and bongs.

By 2003, the Thai government under Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra had declared its own “war on drugs” that demonized addicts. Although popular, the campaign was brutal, with more than 2,200 dead in the first three months, according to Human Rights Watch. It also became prone to abuse, as police conducted arbitrary arrests and intimidated human rights defenders. Former Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte waged a similar campaign in 2016. Rights groups have pegged the death toll at 13,000, many of them children. Both Thai and Philippine police have received U.S. equipment and training.

Today, however, Thailand’s cannabis trade with the U.S. has flipped on its head. One of the biggest challenges that dispensary owners like Chokwan face is a flood of illegally imported American weed undercutting local varieties, not least because of the difficulty proving the origin of flowers on sale. “Thailand was the exporter of the illegal weed into the U.S.; now the U.S. is the illegal exporter of weed into Thailand. It’s hilarious,” says Chowan. “But they are ruining our farmers’ livelihoods because their price is at least half.”

It will take time before local producers can catch up. The question is whether, like most industries in Thailand, cannabis gets overtaken by the big conglomerates. Business in Thailand can be rankly exploitative. In agriculture, for example, individual farmers are typically contracted to grow rice or corn by one of a handful of big agricultural conglomerates for a pre-agreed sum based on the size of their plot. Although below market price, it’s a guaranteed income; most farmers prefer that security rather than risk the vicissitudes of weather, disease, and global commodity prices. The fear is that any Thai cannabis boom will follow this familiar pattern, diluting the benefits for low-income farmers while swelling the profits of the corporate giants.

At present, the uncertain legal status means most large conglomerates are investigating cannabis pilot projects without fully jumping in. This practice gives some existing players a potential advantage. Not least since “growing cannabis is super hard,” says Chowan. “You can have all the money in the world, but if you just don’t get it, you don’t understand it, you’re going to fail miserably.”

Thanisorn Boonsoong knows it only too well. The founder and CEO of Eastern Spectrum Group, one of Thailand’s biggest licensed cannabis producers, has 80 acres of fields and a research and development lab two hours’ drive west of Bangkok. Scores of farmers in sun visors and camouflage pants prune cannabis flowers and hang them on long drying racks. Then, technicians extract the various oils, distillates, and biomass to be sold to licensed manufacturers to make products like fabrics, cosmetics, and gummies. “It’s about marrying our Thai farming experience with Western resources, precision farming, and knowledge of cannabis,” says Thanisorn.

Thanisorn first became interested in hemp when Massachusetts legalized recreational cannabis in 2016 while he was studying business at Boston’s Northeastern University. In 2018, Thailand became the first country in Asia to allow cannabis to be medically prescribed, and Thanisorn saw huge potential for the growth of a wide range of hemp products. “Hemp is the embodiment of disruptive innovation, all packaged into one plant,” he says.

Inside Eastern Spectrum’s development lab, scientists in white lab coats tinkering with glass tubes and steel containers to decipher the best way to extract THC and cannabidiol—a therapeutic component that doesn’t produce a high, more commonly known as CBD—from the 2.5 million spindly cannabis plants the firm grows annually around the country. Since June 9, Thanisorn has seen a “surge” in orders for raw cannabis flowers for dispensaries.

Still, he’s sanguine about the potential for a Thai cannabis bonanza. Studying the American cannabis industry, Thanisorn observed how drastic price volatility meant firms that invested large overheads on expensive greenhouses were the most likely to fail. Three years ago, prices of CBD isolate in the U.S. retailed at $10,000 to $12,000 per kilogram. Today it’s lucky to fetch $400. In Thailand, comparative prices are still upward of $7,000, although likely to plummet if they follow global trends. Eastern Spectrum opted to grow cannabis outdoors in fields rather than under glaring ultraviolet lights; Thanisorn says this model gives Thai cannabis the best chance of being globally competitive.

Eastern Spectrum’s initial plan is to expand to at least 2,000 acres. However, instead of controlling the area centrally, it invites local farmers onto its land and teaches them how to successfully grow cannabis. After three or four crop cycles, the farmers graduate from the program and return to work on their land under a cooperative or contract farming model.

By harnessing such techniques, Thanisorn says it’s “100% possible” for Thailand to become a major player in the global cannabis industry in perhaps three to five years. Obstacles remain, however. Even with lower utility, infrastructure, and labor costs than the West, most Thai growers lack knowledge and experience. And strains popular in North America and Europe grow best in temperate rather than tropical climates. “Thailand still has a long way to go before we’re able to compete with the West on quality,” says Thanisorn. “But on price, we definitely can.”

Even if the quality issue is addressed, there’s a big question mark over how to reach foreign markets. Few Asian nations are expected to follow Thailand toward blanket cannabis decriminalization. Already officials in Singapore and Japan have warned their citizens that they risk being prosecuted at home if they are found to have smoked weed while visiting Thailand. Exporting cannabis to the West would be prohibitively expensive given the red tape and the fact that it could use only routes that exclusively traverse international waters. “The [Thai] government wants us to export, but whom can we export to? Who can import it?” says Thanisorn. “That’s a whole different question altogether.”

A domestic cannabis industry catering to locals and rebounding tourist numbers is a safer bet for now. In the walled northern city of Chiang Mai, joints can be bought at guest house reception desks. Tourists on the resort island of Koh Samui can buy cocktails with cannabis syrup alongside vintage champagne in tony beach clubs.

But the cannabis-boom days may already be numbered. On Aug. 15, the police chief for Bangkok’s Phra Nakhon district said that street hawkers of weed on Khao San Road were illegal and would be prosecuted. (The spur was, somewhat bizarrely, that the Bangkok governor complained of smelling cannabis while jogging nearby.) There are rumors that cannabis businesses will be moved to a single alley adjacent to Khao San Road to keep them out of public view, much like sex work is concentrated in certain “entertainment zones.” Much will depend on a belated law governing cannabis use that is due to be promulgated in the coming weeks.

But even then, the gap between regulation and enforcement is often huge in Thailand. After all, prostitution is nominally illegal but the country has an estimated 250,000 sex workers in prominent, gaudy go-go bars. Whatever the law, the reality of cannabis in Thailand may drift like a haze over Khao San Road. Advocates like Chokwan can only watch and wait. “This is Thailand,” she says with a shrug. “There’s no way of knowing how the authorities will act.”